Last Updated on February 26, 2014

Isabella Blow, the British style icon, fashion editor, talent spotter and muse who died by suicide in 2007 aged 48, is remembered as one of the last true fashion eccentrics, having donned traffic-stopping ensembles before it became a street style norm and social media popularity contest.

Isabella Blow at fashion week, shot by Bill Cunningham in 1999

Isabella Blow at fashion week, shot by Bill Cunningham in 1999

When her wardrobe, one of the most important private collections of contemporary fashion in the world, was to go under the hammer at Christie’s in 2010, Blow’s friend Daphne Guinness stopped the auction by buying the entire lot to preserve the collection for future generations of fashion lovers.

The consequence of Guinness’ surprise gesture is the long-awaited exhibition, Isabella Blow: Fashion Galore!, that opened in November at London’s Somerset House. The show, curated by Alistair O’Neill and Shonagh Marshall, focuses on Blow’s relationship with her most famous protégés, designers Alexander McQueen and Philip Treacy.

The exhibition begins with a selection of Blow’s childhood pictures and press clippings announcing various news about her family. The Delves Broughtons were aristocracy, but Blow never knew the high life because her grandfather had squandered away the family fortune.

Fashion enthusiasts are guaranteed to experience sheer, giddy thrill at the sight of six pieces from Alexander McQueen’s 1992 graduate collection, titled Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims. The clothes are highly reminiscent of McQueen’s later creative direction, fusing the macabre serial killer theme with exquisite, delicate knitwear, glitter and historically inspired deconstructed tailoring. Blow was so in love with this collection that she bought all the garments although it was well beyond her means. She paid McQueen £100 per week and received one garment every month.

Alexander McQueen’s 1992 graduate collection

Alexander McQueen’s 1992 graduate collection

The presentation of Treacy’s 1989 graduate collection is underlined by the play of light and dark, the unusual shapes of hats casting magnificent shadows on the wall.

The next section is dedicated to the Autumn/Winter 1996 season, a turning point in McQueen and Treacy’s careers. They began to outgrow London obscurity, receiving coverage in international fashion media. Blow was the muse for McQueen’s Dante collection and styled Treacy’s show. Seventeen years later, the hats look astonishingly contemporary and could easily be sold as the current collection while the garments would make a stone wail over McQueen’s untimely death.

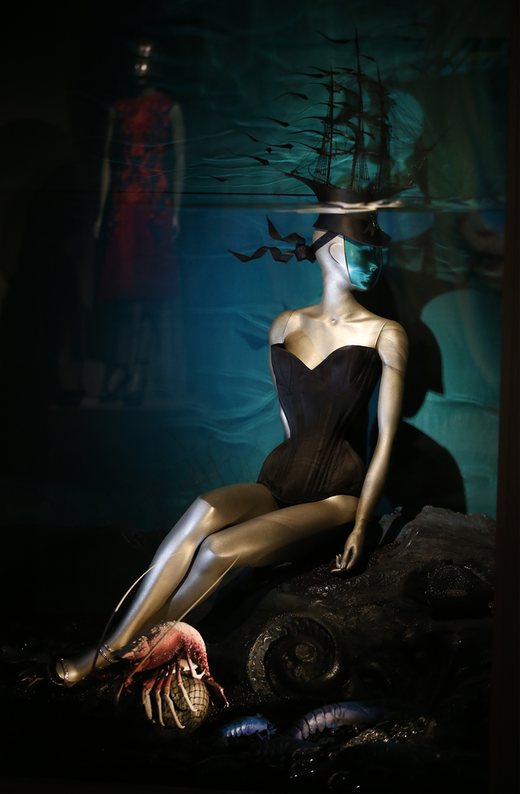

A large part of the exhibition is set in the same space as the Valentino: Master of Couture exhibition. On display are looks by different designers (the infamous pink burka by Jun Takahashi that Blow wore to a Dior haute couture show in 2003 is a showstopper) as well as paraphernalia such as Blow’s Rolodex, business cards from her tenure as fashion director at Tatler and The Sunday Times Style, and a notebook in which she wrote down ideas for shoots in pink ink. The magical window installations by set designer Shona Heath boast the most iconic Treacy hats in the show.

Installation featuring Treacy's famous ship hat entirely made of feathers

Installation featuring Treacy's famous ship hat entirely made of feathers

Exhibitions where garments come from several different designers and seasons seldom achieve cohesiveness, but in this one every piece complements the others — a reflection of Blow’s singular and clear-cut vision as well as smart curation.

A room is dedicated to the London Babes shoot by Steven Meisel (published in British Vogue in 1993). Blow did the styling and casting, putting the spotlight on English beauties Stella Tennant, Plum Sykes, Bella Freud and Honor Fraser. The following week, Meisel invited Tennant to shoot a campaign for Versace and her career skyrocketed.

The final section of the exhibition focuses on McQueen’s Spring/Summer 2008 collection, La Dame Bleue, designed in collaboration with Treacy as a posthumous tribute to their mentor and muse. By the time she died, however, Blow’s relationship with the two designers was no longer as blossoming as the exhibition would have you believe.

Isabella Blow and Alexander McQueen by David LaChapelle

Isabella Blow and Alexander McQueen by David LaChapelle

Blow thought that her knack for sniffing out emerging talent made her entitled to a huge paycheck that would instantly alleviate her financial worries and support her expensive taste. Since no one in the industry was in the habit of giving money to talent spotters, she was counting on her protégés to compensate her for helping them launch their careers once they became established designers.

When McQueen was appointed head designer at Givenchy in 1996 and didn’t secure Blow a creative position with the brand, their friendship began to deteriorate. She was disappointed when Treacy neglected to include her in an anthology on hats. While she didn’t burn any bridges, she did move on to new designers, particularly Jeremy Scott and Julien Macdonald.

“Every queen loves a lobster” (photo by Roxanne Lowit)

“Every queen loves a lobster” (photo by Roxanne Lowit)

In order to paint the subject in the best light (and, presumably, not scare or trigger visitors), any indication of Blow’s long-term manic depression that led to her suicide is absent from the exhibition. Blow’s illness, heartbreaking as it was, is key to understanding her relationship with fashion, the show’s celebratory approach downplaying its complexity.

It’s assumed that Blow’s depression stemmed from a family tragedy in her early childhood. Her parents blamed her for her younger brother’s death and continued to mistreat her until she left home at eighteen. The only childhood memory she recalled fondly was trying on her mother’s pink hats.

From quitting the family home until her death, fashion kept Blow’s well-hatted head above water. She was constantly on the lookout for the next big thing not only because of her desire to promote young talent, but because innovation and outlandishness gave her a reason to live.

Philip Treacy hats

Philip Treacy hats

Outside of the context of her depression, Blow can potentially be dismissed as another rattlebrained aristocrat who didn’t have anything better to do than spend a fortune on kooky hats, but to her, fashion literally meant everything: a defense mechanism (the hats’ duty was to keep people at bay), an occupation, an obsession, a salvation.

There is an extraordinary olfactory aspect to the exhibition: the clothes still smell of Blow’s perfume, Fracas by Robert Piguet. Constantly surrounded by her voice coming from numerous video installations, you half expect to find her in the next room, chatting animatedly to visitors.

Blow wearing a couture kimono (Photo by Getty)

Blow wearing a couture kimono (Photo by Getty)

Daphne Guinness has done fashion a remarkable service by preventing Blow’s clothes from disappearing in private collections all over the globe like the belongings of her predecessor in the marriage of fashion and eccentricity, Marchesa Luisa Casati. Perhaps one day we’ll get to see the unabridged collection that comprises over five hundred pieces.

Of course, the point of the exhibition is to celebrate Blow’s career and life, not only her wardrobe, yet these three elements couldn’t be more intertwined. Would Isabella Blow be Isabella Blow without her clothes and hats? The hallmark of a good exhibition isn’t necessarily answering questions; often, asking them is worth much more.

I really enjoy your blog. All I needed to say.

Thank you - how kind!

The fashion legend, the toast of glossy magazines from London to New York...