Last Updated on July 19, 2022

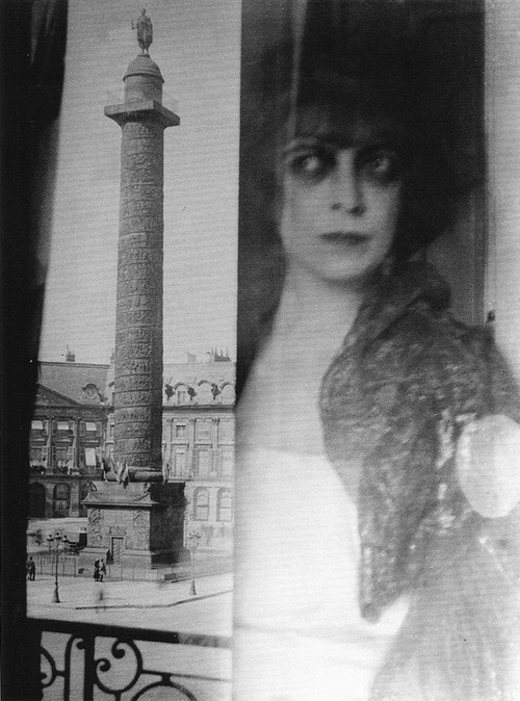

Marchesa Luisa Casati by Man Ray (1922)

Marchesa Luisa Casati by Man Ray (1922)

Marchesa Luisa Casati was an eccentric patroness of the arts and socialite, born into an aristocratic Italian family in 1881. As a teenager, she inherited an immense fortune that she later used to fund her transformation into a living work of art. In her ruined Venetian palace (the same that houses the Peggy Guggenheim Collection) she held legendary soirées, surrounding herself with artists and intellectuals, dabbling in the occult, wearing live snakes as jewellery and parading around the city with cheetahs on jewelled leashes. Her signature look consisted of eyes blackened with kohl, deathly pale face, and crimson-painted lips.

Portrait of Marchesa Luisa Casati by Augustus John

Portrait of Marchesa Luisa Casati by Augustus John

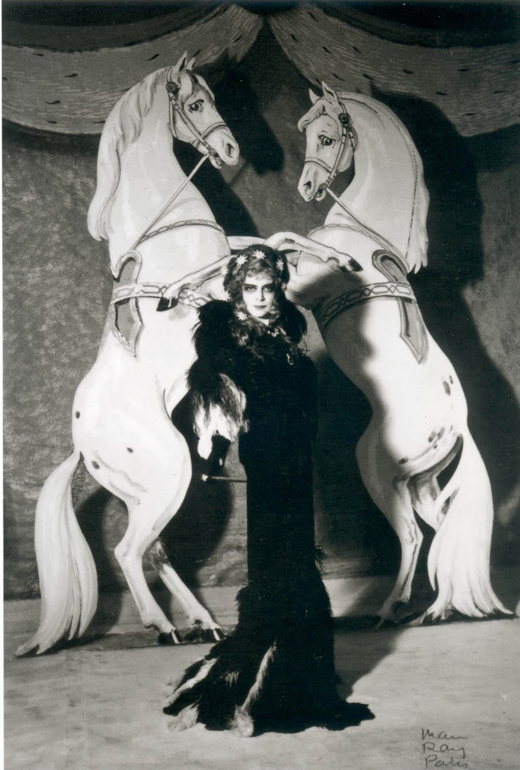

The Marchesa as Empress Elisabeth of Austria by Man Ray (1935)

The Marchesa as Empress Elisabeth of Austria by Man Ray (1935)

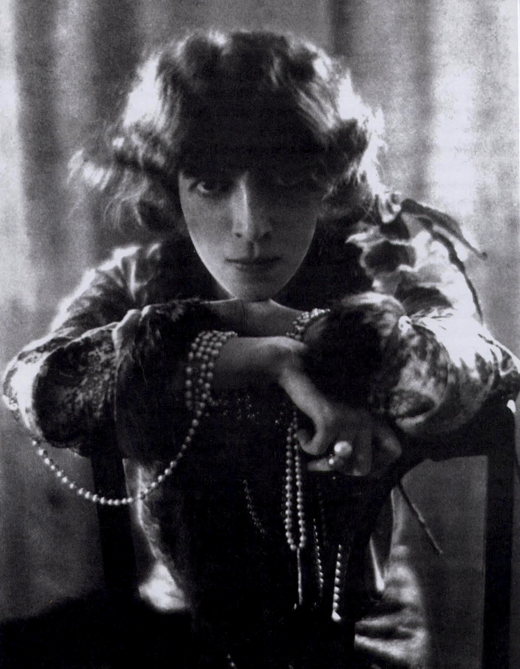

The Marchesa commissioned countless portraits of herself and became one of the most portrayed women in history. Her quest to immortalise herself in art was one of the many things the Marchesa had in common with the Countess of Castiglione, the notorious 19th century femme fatale she had modelled herself on. The Marchesa had lived so lavishly that despite her wealth, she was $25 million in debt at the time of her death, according to her biography Infinite Variety.

Besotted with her mother’s Charles Frederick Worth and Jacques Doucet gowns as a little girl, the Marchesa grew up to become one of the driving forces behind early 20th century haute couture. A patroness and muse to the leading couturiers of the day, she invested exorbitant amounts of money in the best designs and materials. Paul Poiret, Mariano Fortuny, Jean Patou, Léon Bakst and Erté designed extravagant costumes that she wore to dinner parties and high society balls across Europe, often aiming to shock rather than impress.

Marchesa Casati in a fountain costume by Paul Poiret (1910s)

Marchesa Casati in a fountain costume by Paul Poiret (1910s)

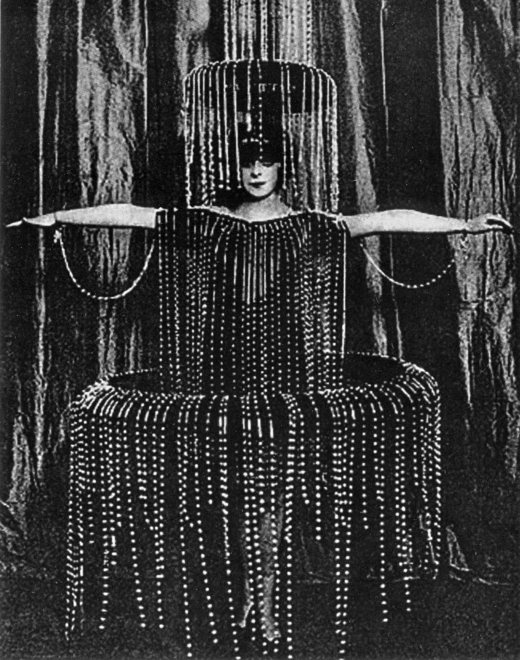

Marchesa Casati in Léon Bakst's Queen of the Night costume (1922)

Marchesa Casati in Léon Bakst's Queen of the Night costume (1922)

One of her most iconic ensembles was the Queen of the Night costume designed by Bakst in 1922 that she wore to a masquerade ball in Paris. Covered entirely in diamonds, the costume took three months to complete. On another occasion, dressed up as the Christian martyr Saint Sebastian complete with electrified arrows, the Marchesa suffered an electric shock and had to withdraw from the party for the rest of the evening.

Naturally, the Marchesa’s outlandish costumes required the company of expensive jewellery. Her favourites were René Lalique, who provided her with bespoke pieces, and later the house of Cartier. The house’s head designer Jeanne Toussaint, who personally delivered jewellery to the Marchesa, was inspired to create Cartier’s famous panther jewel after seeing a stuffed panther in her client’s home.

The Marchesa with artists Paul-César Helleu and Giovanni Boldini in Venice (1913)

The Marchesa with artists Paul-César Helleu and Giovanni Boldini in Venice (1913)

Portrait of Marchesa Casati by Adolph de Meyer

Portrait of Marchesa Casati by Adolph de Meyer

By the time she was fifty, the Marchesa had amassed a debt so large that her belongings had to be auctioned off. From then on, she lived on credit, renting rooms and relying on the generosity of her friends. During the Second World War, she moved to London. The Marchesa spent her last years in poverty, constantly changing addresses, ringing her eyes with boot polish as she could no longer afford kohl, and rummaging through rubbish bins for scraps of fabric to decorate her shabby outfits. Her tombstone in London’s Brompton Cemetery bears an epitaph from Shakespeare’s tragedy Antony and Cleopatra: “Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale her infinite variety.”

Designer Georgina Chapman as Marchesa Casati by Peter Lindbergh in Harper's Bazaar March 2009

Designer Georgina Chapman as Marchesa Casati by Peter Lindbergh in Harper's Bazaar March 2009

Fashion and Marchesa Luisa Casati remain intertwined even after her death with contemporary designers recurrently citing her as the inspiration behind catwalk shows and collections. The British design duo Georgina Chapman and Keren Craig pay homage to her with their high-end womenswear label Marchesa. In the words of Chapman, who posed for Peter Lindbergh in 2009 dressed up as her muse, “the Marchesa Casati was fearless, both in life and fashion. She was self-indulgent in the most empowering way and used her attire to transform herself into timeless walking art. When you are able to dress and live without limits, the possibilities of what you can accomplish are endless.”

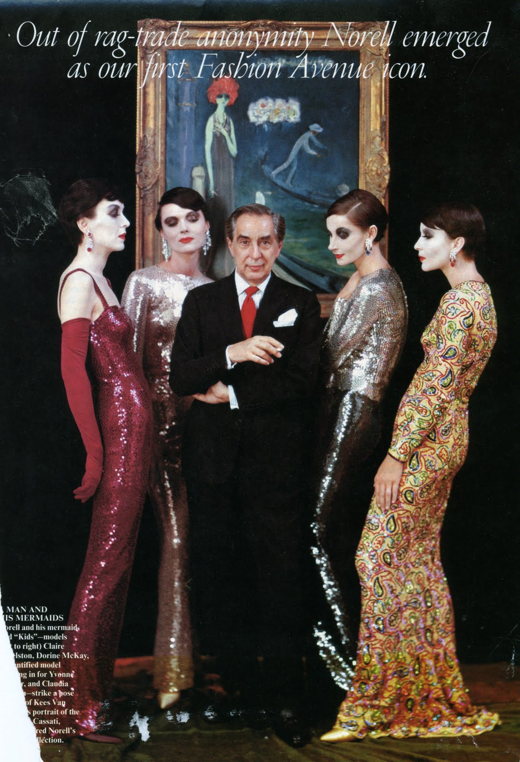

Norman Norell's 1960 collection inspired by Marchesa Casati

Norman Norell's 1960 collection inspired by Marchesa Casati

In 1960, famed American designer Norman Norell presented a collection based on Dutch artist Kees van Dongen’s portrait of the Marchesa standing by the Venetian lagoon. At the time, Norell owned the painting and posed in front of it with his models, clad in sleek paillette dresses and large circles of black eyeshadow, for the cover of Life magazine shot by Milton H. Greene.

Tom Ford saw the Marchesa as “the first European dandy of the early 21st century”, dedicating to her his Spring/Summer 2004 collection for YSL Rive Gauche. At first glance, the collection seemed to have little in common with its inspiration apart from incorporating the Marchesa’s signature kohl-ringed eyes and voluminous ragged hair. Criticised as one of Tom Ford’s worst collections, it (probably unintentionally) hit the right spot with half-naked models. The Marchesa was known to resort to nudity on the odd occasion when men’s attention shifted to other women. In Venice, people were outraged by her late night strolls around the city wearing nothing but a fur coat.

Armoured look from Dior Haute Couture Spring/Summer 1998 by John Galliano (image by Fashionanthology)

Armoured look from Dior Haute Couture Spring/Summer 1998 by John Galliano (image by Fashionanthology)

Dior’s Spring/Summer 1998 haute couture show resembled one of the Marchesa’s extravagant masquerade balls. Set in the Opéra Garnier in Paris, where the Marchesa herself had attended many events, it reportedly cost $2 million to stage. John Galliano designed a romantic collection featuring fur-lined kimonos, veils, lace, and sleek, floor-length gowns heavily embellished with beads and fringe. One model wore a piece of armour covering the whole arm, evoking the Marchesa’s 1925 Cesare Borgia costume. “Although no longer with us, her life stays as a beacon and as a constant source of inspiration,” said Galliano. A decade later, he launched an eponymous perfume inspired by the Marchesa’s first Boldini portrait.

Chanel Resort 2010 show in Venice

Chanel Resort 2010 show in Venice

Karl Lagerfeld paid tribute to the Marchesa with his Chanel Resort 2010 show, appropriately set in Venice on the island of Lido. The glamorous collection was imbued with black, white, and gold (the Marchesa’s favourite colours) as well as references to her life, such as armour-like accessories and snakes. In 2003, Lagerfeld photographed Carine Roitfeld, then editor-in-chief of Vogue Paris, dressed as the Marchesa for The New Yorker. In the accompanying article, he said that “Roitfeld plays a modern Casati, but the drama of Casati was that she was not playing.” Thanks to her sincere and raw quality, Marchesa Luisa Casati will continue to inspire for the years to come.

Beautiful Post! Really loved the story and your writing!

Thank you for the lovely comment!

Long time lurker, first time commenter! I just wanted to say that I loved this article. One of the topics that fascinate me the most is that of people who reinvent themselves, using their bodies and lifestyles as a canvas for creative expression. The way you tied up the Marchesa's story with the fashion collections inspired by her and her antics was really captivating, this is great fashion blogging. Kudos and keep up the great work!

Hi Violetta! I'm really glad to receive such a thoughtful and positive comment from you. Would love to hear your opinion on my posts more often!

What a fascinating woman! You know, she strikes me as rather like the precursor to Anna Della Russo - an individual inextricable from fashion. But I suppose the difference in their trajectories says a lot about how the role of women in fashion has changed. ADR has been able to utilise her outlandish fashion tastes and creativity to build a phenomenal career in a way which, had she been born 100 years later, I think the Marchesa would have done. But ultimately - it seems to me anyway - in a world with no space for female creators, Marchesa Luisa Casati was destroyed by her own creative impulses. This article really highlights how women have taken ownership over their own creativity over the past century, moving away from being the muse and towards being creators in their own right. A great read - thank you for bringing my attention to such a tragic yet inspiring figure!

Hi Elizabeth! Thank you for the incredibly insightful comment. I never thought to make the connection between the Marchesa and Anna Dello Russo. Everything you said makes total sense - we can only be happy that the world today is friendlier and more accepting of female creators.

Following reading/thinking about this, I've actually written a post about fashion and femininity for my blog (www.britishvague.hotspots.co.uk). I would love for you to check it out!